Very few scientific studies concern freemasonry’s history in Haiti. Nevertheless, particularly in the nineteenth century, this association had a considerable influence on the social and political life of the country. Traditionally, most of the Haitian Statesmen attended the Masonic lodges, which, although joining around certain ideological principles, were often politically opposed. Subsequently, the freemasonry can be considered as a space of sociability and power for the political elites of Haiti.

A French trader, by the name of Etienne Morin, had been involved in high degree Masonry in Bordeaux since 1744 and, in 1747, founded an “Ecossais” lodge (Scots Masters Lodge) in the city of Le Cap Francais, on the north coast of the French colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti). Over the next decade, high degree Freemasonry continued to spread to the Western hemisphere as the high degree lodge at Bordeaux warranted or recognized seven Ecossais lodges there. In Paris in the year 1761, a Patent was issued to Estienne Morin, dated 27 August, creating him “Grand Inspector for all parts of the New World.” This Patent was signed by officials of the Grand Lodge at Paris and appears to have originally granted him power over the craft lodges only, and not over the high, or “Ecossais”, degree lodges. Later attempts to disparage the validity of this Patent claimed, without material evidence that it appeared to have been embellished by Morin, to improve his position over the high degree lodges in the West Indies. The political equivocations of the Bordeaux Lodge provide little to support such claims.

In Haiti, the Craft arrived by way of the Grand Lodge of France. In 1697, the Spanish had ceded the Western portion of Hispaniola to the French, and by the 18th century, the colony (then known as “Saint-Domingue”) enjoyed a booming trade in coffee, sugar, and cocoa. With the increased movement of merchants, colonial officers, and slavers, the ideas and practice of freemasonry also became well established. When Haiti won its independence, and utterly abolished slavery at the end of the 1791-1804 Haitian Revolution, masonry was so ingrained into local culture that the all-black revolutionary government inherited the Craft amongst their other spoils of war.

François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture, the former slave who led the revolutionary forces against the French, is himself reputed to have been a devout freemason. His own signature seems to attest to the fact, with its combination of two lines and three dots that mimic a popular masonic shorthand symbol of the time. In fact, masonry was so integral to Haitian culture and leadership, than any president of the country who was not a mason prior to office was ordained on the occasion of their election.

Meanwhile another of Haiti’s founding fathers, Jean-Jacques Dessalines — the Emperor Jacques I of Haiti — was similarly invested in the Craft. The National Museum of History, in the center of Port-au-Prince, houses artifacts such as the slave-turned-emperor’s own sword and scabbard, clearly engraved with square and compass motifs.

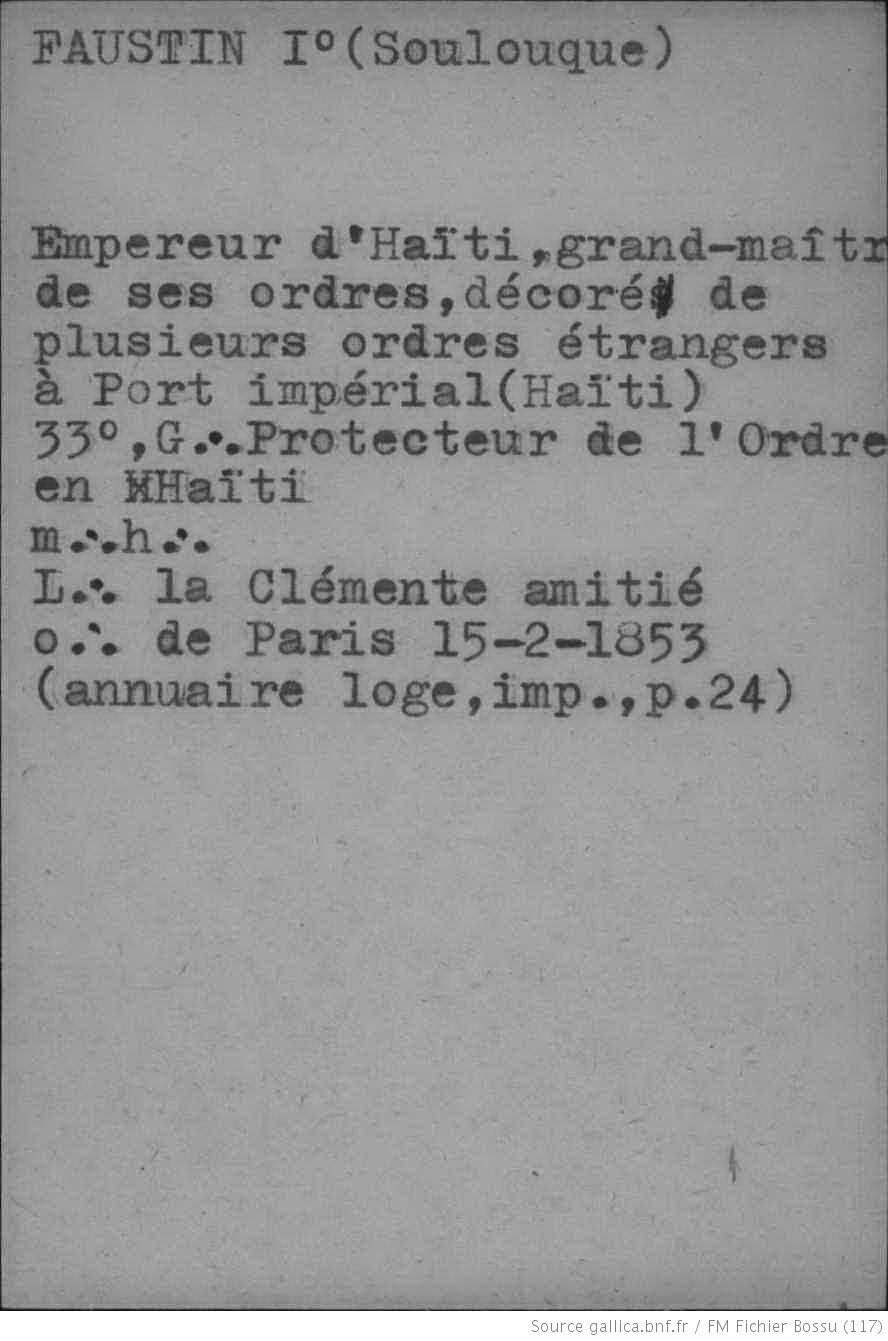

Faustin I was Grand Protector of the Franc-Masonic Order 1850-1859. He was a member of a Masonic lodge in France. This was in tradition with other Haitian leaders. In 1743, after the death of Louis de Pardaillan de Gondrin, duke of Antin, Louis de Bourbon-Condé (1709-1771), count of Clermont, prince of the blood and future member of the Académie française, succeeded him as “Grand Master of all regular lodges in France”. He remained in office until his death in 1771. Around 1744 there were around 20 lodges in Paris and 20 in the provinces.

Grand Masonic Lodge of Haiti

A lavish ceremonial sword was made for Faustin I. It was presented to him by The Grand Masonic Lodge of Haiti in 1850. According to family tradition, Henry Delafield (1792–1875) later received it as a gift from Faustin. Delafield was a prominent businessman who served as Consul for Haiti in New York from 1851 to 1859.

The sword remained in the Delafield family until it was bequeathed to the MET in 2012. The sword is engraved within a cartouche on the reverse of the blade at its base: Robert Mole / Sword Cutler / Birmingham.

Lodges in the provinces were most often founded by Masons out of Paris on business or via the intermediary of military lodges in regiments passing through a region – where a regiment with a military lodge left its winter quarters, it was common for it to leave behind the embryo of a new civil lodge there. The many expressions of military origin still used in Masonic banquets of today date to this time, such as the famous “canon” (cannon, meaning a glass) or “poudre forte” (strong gunpowder, meaning the wine).

Development of freemasonry on Haiti

After independence, the Haitian Masonic community developed links with its counterparts in France, the United States of America, England and Switzerland. In 1835, for example, “the Grand National Lodge of Switzerland received the first overtures from the Grand Orient of Haiti, which resulted in an exchange of fraternal communications between these two Masonic authorities” . Masonic lodges, which were centres of sociability and power, multiplied throughout Haiti.

During the nineteenth century, it was customary for lodges to define themselves not only by a distinctive title, but also by a serial number (#) in the chronology of the obedience.

The development of Dominican Freemasonry encountered some difficulties. Between 1830 and 1844, several lodges were working under the Grand-Orient de Haïti, in Port-au-Prince, as well as in Santo Domingo, Anna (Santiago), Seybo (Plata). Only in 1847 did the Supreme Council of Paris preside over the foundation of the Primatial Lodge of the Scottish Grand Elect. Two years later, this lodge, forced by political circumstances, had to suspend its work. In 1858, several brothers from Saint-Domingue formed a Grand Lodge and informed all the Grand Lodges of Europe of this foundation, asking them to recognize it. In 1859, a new lodge was founded in Anna, and since then, Masonry has returned to the path of progress. Members of the brotherhood include: Pedro Santana, President of the Republic, Thomas Bobadilla, President of the Senate, Léon, English Consul, José Dios, official of the High Court of Justice, Man. Delmant, senator. Naturally, the high ranks were also highly honoured.

The history of Haitian Freemasonry, despite recent notable efforts, is little studied by our contemporaries. Researchers concentrate particularly on the colonial period and especially on the “Masonic plot” during the War of Independence (1802-1803). Indeed, most of the signatories of the Haitian Independence Act were initiates who were to ensure the continued existence of the association in the new state. Is this just a coincidence? Current research shows that many lodges existed in Saint-Domingue. Because of the entrenchment of colour prejudice in society, they were frequented by white French colonists. At the same time, in the second half of the eighteenth century, freedmen were initiated when they travelled to France. They were amongst the first to challenge the colonial and racist order that prevailed in Saint-Domingue. It was from 1793, after the abolition of slavery, that black and coloured officers joined the lodges in large numbers. For example, most of the dignitaries in General Toussaint Louverture’s entourage were Freemasons.

Of course, much remains to be done on the development of Haitian Freemasonry in the nineteenth century.

Sources

- Darmon Richter, Freemasons of the Caribbean

- E.C. Ballard, The Illustrious Role of Haiti in the Freemasonry of the Western Hemisphere

- Leah Gordon, Freemasonry in Haiti

- Corey D. B. Walker, A Noble Fight, African American Freemasonry and the Struggle for Democracy in America

- Mollès Dévrig (éd.), Masonería y religiones, Buenos Aires, Fondo editorial de la Gran Logia Argentina, 2023. The publication quotes the IMIH on page 143.

- Clorméus, L. (2015). Quelques aspects des rapports entre la franc-maçonnerie et la sphère politique en Haïti au XIXe siècle. Outre-Mers, 386-387, 183-204. https://doi.org/10.3917/om.151.0183

- La fédération Maçonique Haitienne